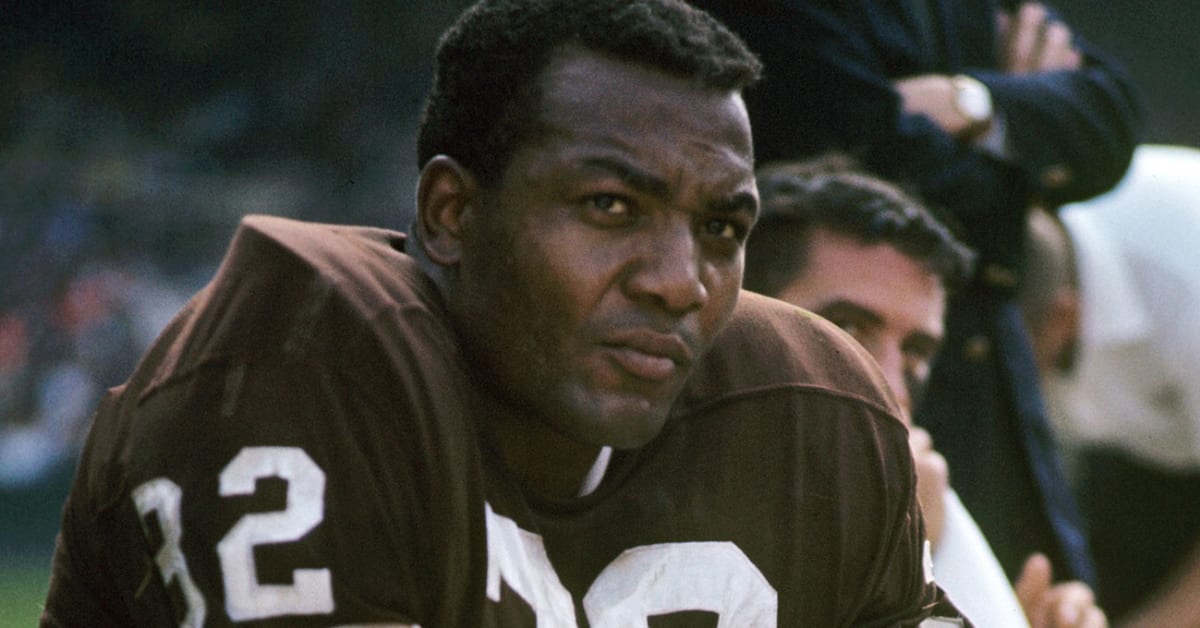

The Greatest Thing About Jim Brown Was the Gap Between Him and Everyone Else

More from Albert Breer: Introducing Josh Harris, the Right Owner to Revive the Commanders

A sleepy time in the NFL calendar will get a little pick-me-up from the Twin Cities over the next couple of days, and we’re here for that. Until then …

We’re going to start with Jim Brown the player, and I’ll never forget how my dad talked about him. When I was a kid, Emmitt Smith, Barry Sanders and Thurman Thomas were among the sport’s brightest stars, and running backs hadn’t yet been devalued. Sanders spent much of that time pacing to break Walter Payton’s rushing record, something Smith eventually wound up doing, and Thomas set the mold for the new age of tailback.

And yes, my dad never let me forget who the greatest was.

The greatest was Brown, who died Thursday at the age of 87.

Context is important here, in large part because football isn’t a sport that lends itself to raw numbers telling the full story. The game has changed too much over the years to compare eras, and for that reason I think the best comps for Brown, as a player, are in other sports.

Namely, I see Babe Ruth and Wilt Chamberlain as his peers—athletes who were so physically dominant in an earlier time for their sports that statistics can’t do them justice. But if you’re insistent on coming up with a numerical measure, like Chamberlain’s 100-point game or Ruth’s 60-homer season (the players who finished tied for third in home runs that year had 30), I think it’s in the gap between Brown and everyone else when he played.

A look …

• Brown won eight rushing titles in nine years as a pro, winning the rushing title in those years by 242, 736, 293, 156, 101, 845, 277 and 667 yards, respectively.

• When he retired, he had seasons No. 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8 and 9 on the single-season rushing leaderboard in NFL history.

• He walked away as the game’s all-time leading rusher, with 12,312 yards. At the time, after the 1965 season, Joe Perry was second with 9,732 yards, Jim Taylor was third at 7,502 and John Henry Johnson was fourth at 6,577.

• He won three NFL MVPs, and a championship during the league’s Vince Lombardi era.

• He’s the only player in NFL history to average more than 100 rushing yards per game over an entire career.

And to kids like me, who never saw him play, there was a Paul Bunyan–like quality to the way Brown was described, very much like you’d hear people talk about Chamberlain and Ruth. Which is why, if you put together a nuanced picture of who Brown was on the field, it’s not hard to get to a place where you, like my dad, would think Brown was the greatest.

Someone else with some credibility once said it, too.

“The greatest football player ever,” Bill Belichick told Sports Illustrated’s Tim Layden in 2015, “no doubt.”

The rest of Brown’s story is complicated. The good of it is all the social justice work he did at a time when it was flat-out dangerous for Black people to do so. The bad came in his personal life—Brown was arrested seven times for assault, and in a number of those cases the violence was against women.

On the former, there’s no denying the difference-maker he was. He was to football what Bill Russell was to basketball or Muhammad Ali was to boxing, as a sport’s most vocal leader in rallying athletes behind the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Brown also helped start the Black Economic Union, which funded Black businesses, and founded the Amer-I-Can Foundation, which worked to rehabilitate prisoners and gang members, and safely integrate them into society, works that Belichick wound up helping Brown with.

On the latter, his record is similarly long. Charges were dropped in most cases, but the disturbing trend of accusations stretches across decades, with the first one happening in 1965 and the most recent one taking place in ’99, involving the woman, Monique Brown, he remained married to at the time of his death last week.

In my opinion, all of it deserves mention, and mentioning one side of Brown’s story should definitely not come at the exclusion of the other side of it. It’s complex. And none of it, good or bad, should be buried or hidden with his passing.

The NFL’s accelerator program kicks off its third session this week, and I do think progress has already been made. Last year, prospective head coach and GM candidates converged on the league’s spring meeting in Atlanta for the first run at it, as we wrote about in detail here. In December, a second session was held, focused on the personnel-side employees. And over the next two days, at this year’s spring meeting, a coach-centric version of the summit will take place.

To this point, there’s been one alum of the program to land a top job—former 49ers director of player personnel Ran Carthon, now the Titans’ GM, was part of both the May and December 2022 programs—and so I figured it’d be good to touch base with him to get a feel for how it helped and how he sees its future.

And maybe it’s best to start with the advice he has for participants ahead of the event.

“I would tell them to be intentional about what they want to get out of it,” Carthon said Sunday. “And definitely take full advantage of the opportunity, and step out of your comfort zone to do that. It’s rare, no matter what your race is, or what situation you’re in, that you get to be in a room with all 32 clubs represented at the ownership level.”

That’s why there was a very clear intention Carthon entered the program with: to expand his network and tear down any walls that might exist between him and owners.

“I’d gone to the program we had at Penn a couple years ago, so I felt like I was going to get a lot of the same information that I did there,” Carthon says. “Obviously, with your experience, you can grow and learn things. But the biggest thing was the ability to network with owners that I otherwise wouldn’t have gotten. Thing was, at Penn, the only owners there were the ones on the panels, as opposed to being with all 31 and [Packers president] Mark Murphy. That’s a big difference.

“And that can be a lot. You’ve heard it referred to as speed dating, and it takes that on when you don’t have a plan, and you’re just trying to meet everyone.”

Carthon went into last May’s accelerator with two goals. First, to meet the owners of the teams that he’d interviewed with the previous January, those being the Bears, Giants and Steelers (the interviews were over Zoom). And to reintroduce himself to the owners of the two teams he played for, the Lions and Colts. He wanted to thank all of them for the opportunities they’d given him and put a face to a name.

What he tried to avoid was rushing up to the owners who’d have open jobs (“I didn’t want to come across as thirsty”) and instead, letting things happen naturally. Carthon was introduced to Titans owner Amy Adams Strunk by a mutual friend at the December accelerator, and had a brief conversation with her. Then, on Day 2, 49ers exec Paraag Marathe invited Carthon to stay with him during one of the league’s winter-meeting sessions, where he saw Adams Strunk again.

Obviously, those interactions didn’t get him the job in Tennessee, but they allowed for everyone to hit the ground running when he interviewed there a month later.

“They were brief conversations, but it made it easier to walk into a room for one of the top jobs in our business,” says Carthon. “There are still nerves, but if you’ve met them before, you’re not walking into a room with a complete stranger. You’re not introducing yourself.”

And in the end, obviously, it all worked out, and, for Carthon personally, going to the accelerator proved a great success. That said, if he could pick something to change …

“I just think for some of us in the room, the assistant GMs, the directors of player personnel, the guys who’ve been through the accelerator, or the Stanford program, the information can be redundant,” Carthon says. “I think as we grow, expanding the curriculum, or tiering it to where, if you’re an assistant GM, you don’t go through the entry-level stuff on the cap would be good. Why not use that time to talk to current or former GMs?”

But all in all? I think the well-intentioned program is off to a good start, and Carthon is proof of it.

Ryan’s second act did not last as long as some other QBs who moved on to new teams.

Robert Scheer/Indianapolis Star/USA TODAY Network

Matt Ryan is a great example of how fast it can go for players. A year ago, I was pretty convinced that, in Indianapolis, he’d found an ideal home, and I know the GM and coach there at the time (Chris Ballard and Frank Reich, respectively) felt like the idea of a Peyton Manning– or Tom Brady–style second act, one that would last three or four years, was in play.

This story from last June probably reflects that nicely.

So what happened? A few things, I think.

First and foremost, what seemed like a great spot for Ryan most certainly wasn’t one. The team’s once-strong offensive line came apart. Then, an unease with the team’s core aging (and seemingly getting further from, not closer to, a championship) took hold with owner Jim Irsay, who benched Ryan one week, facilitated the firing of offensive coordinator Marcus Brady the next week and fired Reich the week after that.

In the end, Ryan got seven starts for a team that was coming undone, then five more later in the year for one playing out the string. And in that time, it was easy to confirm the feeling the Falcons had: that his arm strength, which was good-not-great to begin with, was in decline, and that he simply couldn’t move well enough anymore.

“He was done two years ago,” says one rival quarterbacks coach. “But he actually played really well early in 2021, and kept a really bad roster competitive. … He’s just old. His arm was never that strong, but now it’s Chad Pennington–ish. And he’s a statue.”

Plenty of folks felt that way about Ryan. Then again, many thought that of Manning coming off his neck surgeries, too, and even well into his first season in Denver. Manning adjusted in time, and made it work, playing in two Super Bowls as a Bronco. I’m not suggesting here that Ryan would’ve ended up doing that in Indy. I’m just saying he was never afforded the chance to.

And so that’ll likely be it on a really good career for Ryan.

Here’s hoping everyone remembers the player who was enormously important for the Falcons franchise in 2008, and the player who, when things were right, played like a top-five player in the sport, as evidenced by the MVP he won when Kyle Shanahan was his coordinator in ’16. I think, for what it’s worth, he’ll be pretty good in the broadcast booth.

This week’s league meeting got a whole lot more interesting with a burgeoning brawl over the kickoff touchback rule. If you missed it, go read our story on all this from Friday—where we detail how special teams coaches and players have organized to try to shoot down a healthy-and-safety rules change they believe will actually create more injuries by virtue of generating bad football on squib and corner kicks.

The NFL has a vote on the matter set for 12 p.m. CT on Monday. Two months ago, at the league’s annual meeting, the proposal was tabled.

And, to me, just as interesting is a relatively widespread theory that owners want to be able to use this rules change as a red herring, as they push the Thursday Night Football flex through. The TNF flex was pushed hard by commissioner Roger Goodell in March, but fell two votes shy (24 were needed, 22 voted yes, and Carolina and Denver abstained) of what was needed, even as the league furiously tried to adjust the rule to get it passed. There are, of course, health-and-safety concerns tied to the TNF flex.

So passing the other rules change would give the owners something to point to in order to “show they care,” while actually taking care of Amazon in enhancing the TNF package.

If it all seems a little grimy, well, welcome to the NFL.

There are other matters of interest to fans to be discussed in Minneapolis. At least, that is, if you’re into the minutiae of the NFL. A few things on the docket …

• The NFL will vote on awarding Super Bowl LX to the Bay Area. The Big Game was there 10 years ago, with San Francisco serving as the hub for events, and the game about an hour away in Santa Clara.

• The Jets’ proposal to enhance rules on crackback blocks, another one tabled from March, will be voted on during that 12 p.m. CT session Monday.

• There are 50 minutes devoted there to international matters, with NFL Africa on the agenda.

• The TNF flex isn’t the only broadcast matter to be voted on. The wild-card playoff game going to Peacock (more on that in a minute) will be, too.

• The Tennessee stadium agreement will go to vote. The Titans’ new home is scheduled to be ready for the 2027 season. (I’d bet they’ll get Super Bowl LXIII, which will be a blast.)

• There’s a two-hour privileged (owners only) session scheduled for 10 a.m. Tuesday. Presumably that’ll be where the Commanders sale is discussed, in earnest.

The Peacock wild-card game is about money, and it’s about the future. And to explain that, we’ll give you a history lesson. About a decade ago, the big networks were trying to level up their cable arms, and it was happening right around when the NFL was expanding TNF to a full-season product. Those networks planned to bid on TNF with the hopes of using it to prop up their cable networks.

The NFL’s response? In a nutshell: You won’t be using TNF to prop up your cable networks. We’ll be using your over-the-air networks to prop up TNF.

The idea, of course, was to ensure that Thursday Night Football got to the biggest audience possible, which would eventually turn it into a more valuable property for the NFL to sell. And eventually, that led to the league selling it to Amazon.

So why would the league risk losing so many eyeballs for one of its wild-card games by moving it to a streaming service most football fans would have trouble finding? Again, it’s money, and it’s the future. To know why it’s the future is simply to look at how people 25 and under are consuming content—so there’s benefit in conditioning people to watch over streaming now, before things really flip.

That said, the biggest benefit to the league is in that nine-figure check that the NFL was able to generate out of thin air, simply for allowing NBC to use one of its playoff games to compel people to subscribe to Peacock.

Always smart to follow the money, in trying to understand the NFL’s moves.

The Patriots’ release of Yodny Cajuste garnered very little attention last week, but it was a mark in why New England’s declined over the last couple of years. That transaction meant that every player from the team’s draft classes of 2018 and ’19 are now gone. It also means that just three players drafted by the team before ’20 are still around: DE Deatrich Wise Jr., LS Joe Cardona and special teams ace Matthew Slater.

And another staggering fact? Of the nine first-round picks the Patriots had from 2010 to ’19, only two are with any team right now. One is Chandler Jones, drafted in ’12, with the Raiders. The other is Isaiah Wynn, who did a one-year, make-good deal with the Dolphins last week, after washing out of New England and sitting on the free-agent market for two months.

Maybe this isn’t as big a reason for New England falling off as losing Tom Brady was. But it’s definitely significant, and only underscores how vital the prosperity of more recent classes that include Mac Jones, Christian Barmore, Kyle Dugger, Josh Uche and Cole Strange is.

Bottom line, if the Patriots turn it around this year, it’ll have to be because a bunch of young players broke through for them, with Jones’s progress being no small part of that.

Mitch Trubisky can say it: God Bless America. Because being a solid NFL backup can be, indeed, a pretty good way to make a living. The second-year Steeler redid his contract last week and signed a new three-year deal to stay in Pittsburgh. He’ll get $8 million in the first year, which is a really nice chunk of change for a player who, if things go according to plan, won’t take a significant game snap all year.

It’s a good lesson for young players, too, on the importance of being a good person. Trubisky got benched last year, but remained a solid resource for Kenny Pickett, and became someone the Steelers wanted to keep around because of how healthy their QB room was.

In many ways, Josh McCown is the standard for this sort of thing. Thought to be in his twilight over a decade ago, McCown returned to the Bears in emergency seasons in consecutive years (2011 and ’12), literally coming off the sidelines from a job coaching high school football to do so. He played the full year in Chicago in ’13 as a result and was instrumental in helping coach Marc Trestman install a new system.

The upshot, from there? Because he was seen as a good person, a good resource to a starter and a good soldier for a coaching staff, McCown wound up playing seven more seasons in the NFL, after those three in Chicago, and he made about $35 million over those years.

Good work if you can get it. And Trubisky apparently has it.

Jadeveon Clowney has quietly shown, over the past few years, how, for more players than not, one-year deals are the best way to go. That much hit me this week, when Clowney told KRIV-TV in Houston that he’d be open to returning to the Texans.

I’d almost forgotten Clowney’s still out there as a free agent.

But this is how he’s done business—and business, for him, has been pretty good.

I was at Clowney’s first game as a pro in 2014, a game in which he stepped in a seam in the old NRG Stadium grass and blew out his knee. He needed microfracture surgery, and a lot of folks think he lost that day the extra gear of explosiveness that made him so special in college, and never really got it back. I think something else happened, too: He really became an independent contractor after going through the aftermath of the injury, knowing that no team would really have his back.

The Texans tagged him in 2019, and traded him to the Seahawks that summer. Since then, he’s played on three one-year deals, one in Tennessee, and the last two in Cleveland. Over those four years, through which he maintained his flexibility and freedom, he’s pulled down around $46 million. And that’s even though he’s been hurt and had just 14 sacks total over that time.

Now, he’s 30 years old, and someone will probably get desperate and throw him another one-year, eight-figure deal, and he’ll get to do that deal on his own terms, after getting to spend the offseason working out on his own (as he has the past few years).

Of course, I’m not suggesting that this is the right way for everyone. If someone offers you what, say, T.J. Watt got in Pittsburgh or Myles Garrett got in Cleveland, you take it 10 times out of 10.

But if you’re the next tier down from that? Handling your business like Clowney has, where you’re always able to take advantage of an ever-escalating market and needs of teams as an offseason evolves, isn’t a bad way to go.

Clowney hasn’t lived up to the expectations set out for him before his injury. And yet, he’s pulled down $80 million over his nine NFL seasons. And counting. And there’s reason for that, which go well beyond what kind of football player he is.