- Published: 18 July 2023

- ISBN: 9781761340055

- Imprint: Viking

- Format: Trade Paperback

- Pages: 400

- RRP: $35.00

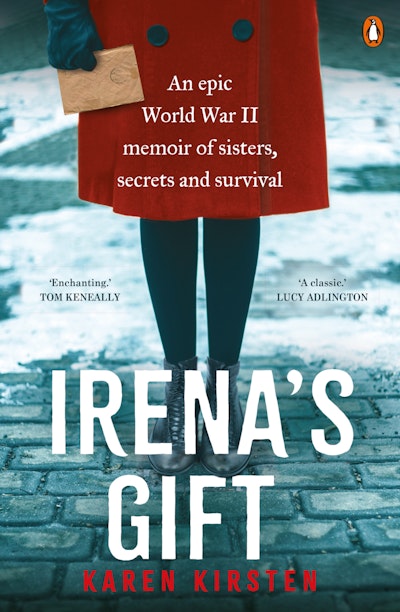

Irena's Gift

An epic World War II memoir of sisters, secrets and survival

Extract

Magpies warbled in the gum trees as we walked up the path to Nana Alicja’s ground-floor flat in the upper-crust Melbourne suburb of Toorak. I pushed the buzzer, then heard Nana’s poodle barking and sniffing beneath the door, the donk, schlep, schlep of Nana shuffling down the hallway with her walking stick. As the door slowly opened, I sensed my mother beside me bracing herself. ‘What you have there?’ My grandmother raised her head of perfectly coiffed, auburn-dyed hair as far as her bowed shoulders would allow. She smiled at me warmly, but barely acknowledged Mum.

I levered open a box containing cakes we had selected from Nana’s favourite patisserie: a hazelnut meringue gateau for Nana, mille-feuille filled with creme patissiere for Mum and me, and strawberry tarts for us all. Nana inhaled the rich vanilla scent. ‘Mmmm!’ she said, grinning. She brushed off my mother, who was trying in vain to peck her on the cheek, and made her way back down the oil-painting-lined hallway to the galley kitchen that smelled of beef fat and carrot. Nana’s part-time Polish caregiver had made a stew.

I followed Nana and arranged the cakes on a platter while watching Mum in the lounge room trying to calm the dog. As Nana reached into a cupboard for her gold-rimmed china, light streamed in from the courtyard and caught the blue-green numbers tattooed on her forearm: 2 4 5 3 3 5, though they’d softened over time, morphing into her skin folds and sunspots.

I was four or five when I first asked about the numbers. I was sitting with my younger sister, watching Nana Alicja chop beetroot and onions for a soup. Nana’s knife hit the cutting board: rap, rap, rap. She tilted her head high to prevent the onion fumes stinging her eyes.

‘It’s our phone number,’ Nana said. ‘So I won’t forget it.’

‘Who put it there?’

Papa Mietek poked his nose over his newspaper.

‘Oh, just some man.’ Nana scraped the onions into a pot. She put down the knife and passed us a tin filled with European chocolate biscuits.

I often suspected Nana Alicja wasn’t telling the truth. On her birthday we’d stand around her Edwardian mahogany diningroom table delicately forking her freshly baked strawberry and meringue cake from her best china. I’d ask how old she was. ‘About fifty,’ she’d reply nonchalantly. Every year.

Papa Mietek would pour champagne into flutes and pass them around to the adults, then to my sister and me, with just enough for a toast. ‘Sto lat! Sto lat! Niech żyje, żyje nam!’ — One hundred years! May she live one hundred years! we’d sing in Polish.

We were never sure of Nana’s age, or what she looked like when she was young; there were few photos of her. It didn’t occur to me back then to read anything into the absence, and, besides, Nana treated me like a princess. She’d bake me cakes, shop with me at Polish and Hungarian food stores like The Chocolate Box in Camberwell, dress up to take me to the ballet and Chopin concerts, and collect seashells with me on the beach with her poodles. I didn’t want to question her stories. I was too busy basking in her love.

Now Nana’s poodle was licking my leg in her kitchen.

‘I like zis hair.’ Nana nodded at my new bob. She always took an interest in my appearance and made approving comments of the sort she rarely made of my mother. ‘Put cakes in lounge room,’ Nana commanded.

I joined Mum and placed the platter, cups and silver cake forks on the coffee table, then poured Nana a strong cup of French press as she slowly lowered herself into a recliner. Mum moved the platter to make room for Nana’s cup. My body tensed – I knew what was coming.

‘Don’t touch zat!’ Nana barked as my mother retracted her hand.

Nana often lost her temper at Mum for no reason, criticising her and snapping. My father had nicknamed Nana ‘The Dragon’. I would stay silent during these outbursts. Perhaps I held my tongue because Nana’s behaviour scared me, or because I knew by then that she had suffered unspeakable horrors in Auschwitz. Maybe, too, I felt flattered she spoiled me. Perhaps it was easierfor me to justify because I was never on the receiving end of her fury.

To this day, I still don’t understand why Mum bothered to visit Nana Alicja every week only to be humiliated. Now I feel ashamed I didn’t speak up for her. Once, after witnessing Nana’s spitting insults, my sister-in-law asked Mum why she put up with the treatment.

‘Because she is my mother,’ Mum said pragmatically.

But the problem – as we knew by then – was this was only partially true.