Today, I’m chatting with Ted Fischer, a professor of anthropology at Vanderbilt University. I’ve mentioned Ted’s work on the show before: He gave a pivotal talk at a 2019 coffee conference that left me questioning so much about the industry, and he’s just released a book called “Making Better Coffee.” In his book, Ted breaks down the history of coffee-growing in Guatemala by looking at Indigenous Mayan farmers, who were displaced by German colonizers in the 1800s and forced into the country’s mountainous highlands. The German colonizers dominated production during coffee’s first and second waves, but the third wave brought attention to—and new tastes for—the high-altitude coffees grown in the areas where Mayan communities had been displaced.

As Ted recounts this history, he argues that great coffee isn’t just about flavor and quality. We’re constantly updating and defining the parameters of quality, and our idea of what makes coffee “good” can be just as much a reflection of our social and political views as it is about what’s in the cup. In this conversation, we talk about how neoliberalism has influenced the way coffee is bought and sold—and how the most powerful actors in coffee now aren’t the ones who own the means of production, but rather the people who can translate coffee’s symbolic value.

This is a chewy episode with many big ideas—you don’t have to read Ted’s book to follow along, but I can’t recommend it enough. Here's Ted:

Ashley: Ted, let's have you start by introducing yourself.

Ted: My name's Ted Fisher and I'm a professor of anthropology at Vanderbilt University, which is in Nashville, Tennessee, where I also direct our Institute for Coffee Studies.

Ashley: I think we're all gonna wanna enroll there after this episode. I know that some people are familiar with the UC Davis program, but I didn't know that there was another Institute for Coffee Studies over at Vanderbilt, which is so exciting.

Ted: Well, it's interesting. It started in 1989, funded by industry interest, in our Department of Psychiatry. And a lot of the work that has bubbled up over the last, I guess 10, 20 years, about the health impacts of coffee, a lot of that got its original start at the Vanderbilt Institute.

Ashley: That's so cool. There's so much cool stuff that I think we're gonna talk about in this episode.

You wrote a book: It's called Making Better Coffee, and I have it open in front of me right now, and I even, as I was thinking about this episode, I was like, “People are gonna hear me just ripping through the book, looking for quotes, things that I wanna ask you about.”

But we're also gonna talk about some of the talks that you've given because for me, I have this really seminal moment where I saw you give this talk at a coffee conference called Re:co in 2019, and you put this one chart up that just completely blew my mind, and we'll get into that in a little bit.

But I wanna start this episode kind of where I start a lot of my episodes with my guests: Did you grow up with coffee in your life?

Ted: Well, it's interesting. I was a coffee drinker, I guess, probably in high school, a little bit in college. I first really started drinking coffee when I moved to New Orleans for graduate school. I did my PhD at Tulane, and there was a PJ's Coffee shop, a specialty coffee shop on Magazine Street that had this little back patio, and I would sit out there all day and all night drinking different kinds of coffees.

This was the early ‘90s, so maybe an Antigua or maybe a Blue Mountain. But first getting introduced to the varieties of coffee. And I think you'll appreciate this coffee shop life, right? I could just watch the rhythm of the city go by sitting on that back patio of PJ’s.

Ashley: I think that's one of the greatest pleasures of visiting coffee shops, is just being able to sit and watch people come in and out. I love that you identified that, but what made you want to study coffee further?

Ted: I am an anthropologist and my specialty has been Maya communities in Guatemala. In Guatemala, about half the population is Indigenous or Maya peoples. And I had been interested in this since graduate school and looking at ways in which Maya communities interacted with the global market.

And I thought I had a really good handle on coffee. I had this image in my mind of awful exploitations on huge plantations that everybody saw as a real negative. And that was my image of coffee in Guatemala.

One time I met with a coffee guy and he was saying, “No.” This was around 2010. He said, “The market has changed completely in recent years. And all those old plantations are slowly going out of business and a lot of Mayan communities are growing coffee.”

I didn't quite believe it, but I was like, there's enough of a story there that I need to dive deeper, and that's when I really started researching this book.

Ashley: To give people a little bit of context about how the book is framed, it does take a lot of your expertise in Maya communities and uses the framework of coffee to understand what's been happening in Guatemala for centuries, essentially.

Ted: Yeah. At least 150 years.

Ashley: I was wondering, maybe this is hard to do, but what would be your elevator pitch about what this book is about?

Maybe it's a long elevator ride.

Ted: Well, it's a hard one for the reason that you said: The threads of coffee extend to so many aspects of life. Our individual health, our relationship with the environment, the political systems that create these contexts in these markets. And so that was an issue that I struggled with in writing this book.

It's like, “How do you follow enough of those strings that are all really significant and yet make it into a common story?” And what I ended up sort of focusing on is the relationship of value and values. When we say “value” in the singular, we usually mean economic value, price. And when we say “values” in the plural, we're talking about moral and cultural and social and political values.

And what I saw with Mayan farmers and what I saw with specialty coffee professionals was trying to to translate between “values” and “value.”

Ashley: Absolutely. I think probably one of the mic drop moments for me, and you reiterate this throughout the book, is that really where third-wave coffee kind of garners its value is not necessarily in the coffee itself. Not in the coffee as a product, but the way that it's able to translate symbolic value, the way that it's able to tell a story, the way that it's able to say to people, “This is better because of X, Y, and Z.”

I think for me that was such a mind-blowing moment because it wasn't necessarily about who's growing the coffee, who's making the coffee, or the coffee itself: it's who is able to translate that value and say to consumers, “This is what this means.”

Ted: Exactly. So well said. I wish you had written the preface to to my book.

Ashley: I'm available for your next book if that's—no, I'm kidding.

Ted: That's exactly right, and I think it's no coincidence that specialty coffee and third-wave coffee took off when it did in the ‘90s and the 2000s, because I think that was also a cultural moment where we're hungry to have products that aren't alienated—to use a term that the Marxists use a lot—that to have products that we know the history of.

The example of that “Portlandia” episode where the couple are asking about the biography of the chicken they're about to eat, is kind of the extreme example of that. But I think it comes from a good spot of us wanting to have some kind of connection with the people who are making the products that we consume.

Ashley: It's interesting that you mentioned this kind of Marxist alienation language, because from what I remember from the idea of Marxism and how the means of labor and production are controlled—it's that having the means of production, controlling the means of production means that you control the value, that you control how things are marketed, and you really have the power.

And you see that through Fordist models—Henry Ford had the means of production. He had all of these factories and he was able to control what the value of cars were and labor was interchangeable. But when you look at coffee, farmers control the means of production. But we’re in this late-stage capitalism where that's been transformed, where the value is not necessarily about controlling the means of production, but controlling the way those means of production are translated to consumers.

Ted: Exactly right. Once again, very well said. And think back—Marx was writing in the 19th century in the Industrial Revolution, and they were putting small, household-based weavers out of business with these big water-powered and steam-powered mills. They lost control over their means of production and had to sell their labor to a big factory.

So that's exactly right. That was the heart of power in that industrial system. And now we are in this new phase where it's not just about control: It's about controlling the narrative. And I would add the means of distribution. So I mean, who has more power? Some small factory in China making a trinket or Amazon, which has the power to reach into people's homes and laptops and market that?

We really are in a different economic phase.

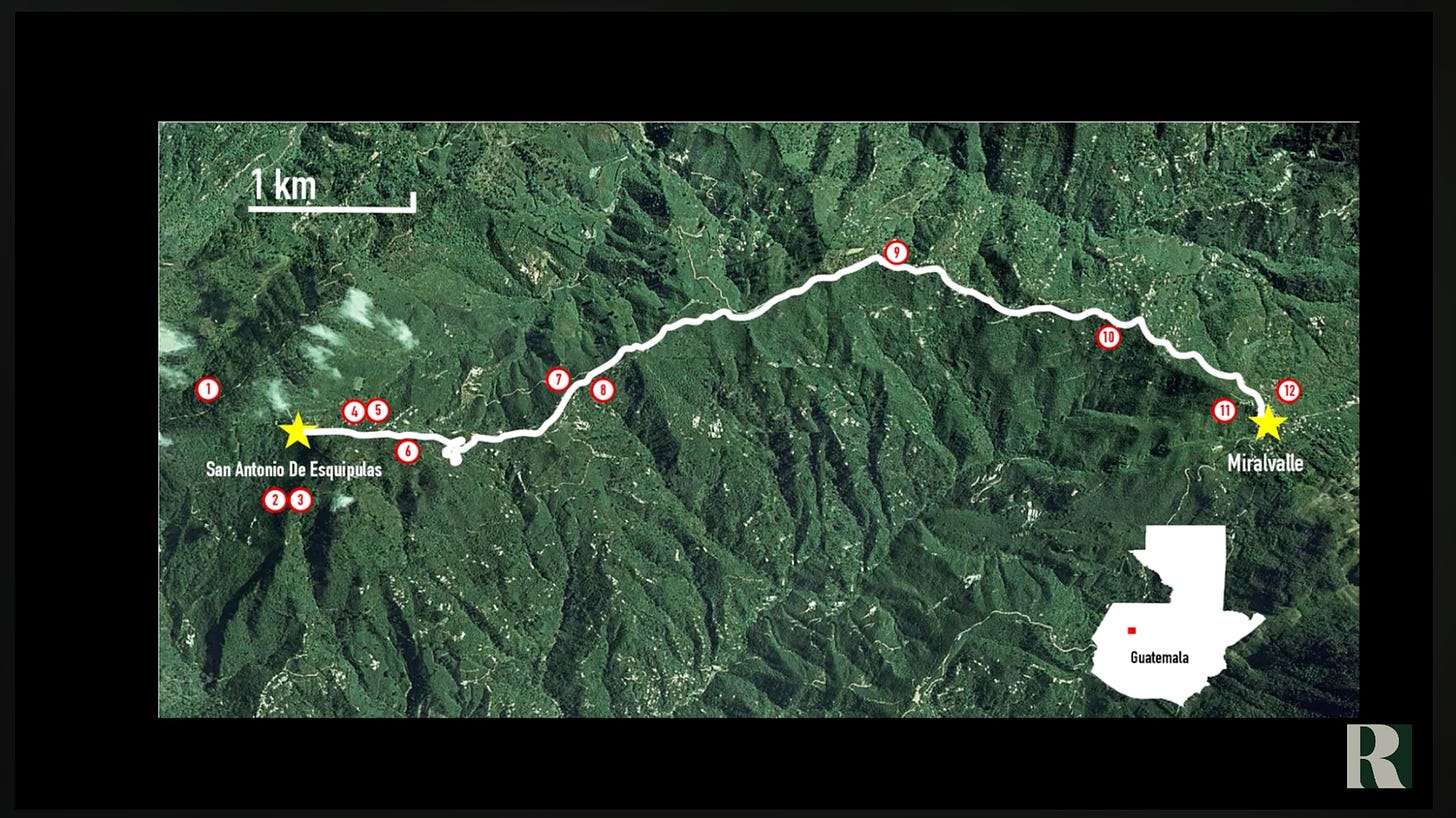

Ashley: I want go back to that talk that you gave at Re:co in 2019, because I think what you just said ties in strongly to this map that you put up. So you were talking about, I would argue, some of the foundational work that you were doing probably with this book that you were writing, you were talking about Maya farmers and you were talking about how value is created and you put up this map and I'll never forget it.

And you identified one farm, I believe, maybe this was in Huehuetenango. I'm not 100% sure.

Ted: Yeah.

Ashley: Okay, so we're in Huehuetenango, which is a region of Guatemala known for producing really beautiful and excellent coffee. And on this [map] you marked a couple of different farms. You numbered them maybe one through 10 and then you had a star on another farm and you were like, ‘This farm with a star is a Cup of Excellence winner.’

And you said that the average price that they get for their coffee is something like $4- something per pound. And you have all of these other farms surrounding that farm that are getting significantly less.

Ted: Like $1.15, four times as much. And that's exactly right. And the smallholding farmers are mostly Indigenous. And the Cup of Excellence farm is a non-Indigenous-owned farm. And that means a lot in Guatemala. Ethnic tensions are quite high.

So you had all these Mayan farmers, same elevation, same microclimate. We bought green beans from them and had them blind-roasted at the National Coffee Association, Anacafé. And they were scoring—I mean, some of them were not scoring high, but over 70% of them were scoring 86 and above. They were producing coffee that on its face should be also worth $4 a pound, and yet they're getting $1.15.

Ashley: Can you explain why that is? As I said that question, that sounded like a ridiculous question for me to ask, but that opens up the question of what market access means, and like you were saying, the means of production and value is not so much about owning the actual means per se, but owning market access.

Ted: That's exactly right. And on its face, you would think that these smallholding Mayan farmers would have all the narrative and the symbolic and the cultural capital to really take the high value out of this [coffee]—they have a millennia-long tradition of farming. They're doing this using traditional cosmological practices in so many ways, and they're producing great coffee in so many ways. That should be a story that consumers would want to buy.

We talk about access and the Cup of Excellence and it has lots of great things to be said about it. And I think it's a neat scheme, but it is an auction to identify the best producers in a country and they make a big deal about saying anybody can enter. And that is true, anybody can enter. But you have to know how to go to that website, right? And figure out what the rules for entering are and know where to send your coffee. All of these things that require a lot of what we in anthropology would call social capital, knowing how the system works—and rural, marginalized, Maya-speaking farmers largely don't know how the system works.

Ashley: Now that we've talked a little bit about Cup of Excellence, I think this is a good time to talk about a bigger theme in your book, which is about the third-wave neoliberalist structure—that's a big term, so maybe we need to break that down a little bit.

But the idea that third-wave coffee is about identifying these really excellent coffees—but at what cost do we do it and who do we harm in the process? So I was wondering, maybe we can take a step backwards and define what neoliberalism is because it does show up a lot in your book, and it is a framing technique you use to describe the third wave.

So I was wondering if you could kind of define what that means and how it applies to coffee.

Ted: Sure—and it is a term that gets used a lot in sociology and anthropology and in the social sciences. Usually you would spit after you say it because it's generally a pejorative…

Ashley: It’s not a nice word.

Ted: It need not be that way. It's an idea that really got hatched in Vienna after World War II and a lot of economists sitting around saying, “Boy, this Soviet system is scary—based around central planning, and we need to go back to our Enlightenment liberal roots that really focused on individuals and letting individuals be free to transact with whom they want to transact with.”

So that's the philosophical view of neoliberalism: really based around individual freedom and liberty. But the way it gets worked out in policy is a reduction in the state, reducing state regulation, letting “free”—and I'm using air quotes there since we're on radio—”free” markets do their work.

But of course, the reality is markets are never free. We need legal systems that back up markets. They're free—but it’s within a certain context.

Ashley: Right, and it's free within your access to it, too, like we were talking about earlier: A market's not free if you don't have access to it. And there's a point too where you talk about the privilege that many Guatemalan farmers, many of these larger farm owners that kind of categorize first and early second wave, almost feel like reluctant to talk about because there's so much faith in a free market regulating itself.

But there's so much privilege that comes along with that.

Ted: Exactly right. And we have to address that kind of structural exclusion or privilege that you speak of with the Mayan communities that I'm talking about. Often people are, first language is an Indigenous Mayan language, and they speak Spanish as a second language. Very few to almost nobody speaks English in those contexts.

And so you have these systems, the Cup of Excellence, it's open to anybody and yet you've gotta have a smartphone. These are super poor communities. You have to be able to know how to fill out forms online. These seem like really basic things but they're huge barriers. And yet the line is—and it's not a totally empty line—but the line is, it's open to anybody.

And if they decide not to enter, well, that's on them.

Ashley: Right. But then that fools us into this idea that we found the best, we did it because we opened it to everybody. And I think that there's something interesting about exploring that fallacy of neoliberalism, making it seem like we made it free for everybody and the market will regulate itself and everything's available to everybody. And when individuals do succeed in a neoliberalist structure, that means that those are the best. But what I think neoliberalism does really well is disguise those limiting factors.

Ted: Exactly. And you asking that question—another thing that I would like to talk about, if not now later, is this idea of discovering the best.

Ashley: Yes! Let’s do it now!

Ted: We put so much emphasis on that discovering part, right? And we have coffee professionals and buyers—they're just like anthropologists when they talk about going to origin and the out-of-the-way places and how tough it was to get there and how awful the living conditions were.

But! We discovered this magical coffee in these remote, exotic places. Yet what that's hiding is that we're kind of making up what the good tastes are as we go along. When I first started drinking coffee—I mean, what's hip right now? The taste of many anaerobic [coffees] or even natural—so an East African natural would've been considered weird, if not defective, and now it's celebrated.

Ashley: Yeah. I think you say that pretty often in the book: You acknowledge that tastemakers—I think I wrote this down. This might actually have been from a different interview you did that I was reading online, but I wrote down, “Tastemakers talk about quality as an objective trait,” which is absolutely false.

Ted: That's right. We're deciding what traits, what flavors, what taste gets celebrated, and that changes from year to year and season to season. And partly for good reasons: I think you and I would agree that kinda hunting out new flavors and, “Wow! Did you know that coffee could taste like that?” That's cool. It's a virtuous pursuit, but it can hide the fact that it's about us and not about any innate qualities in the coffee bean.

Ashley: That's a good point. I think turning it around on us is a really salient point and something that we should consider when we're thinking about the idea of “good” meaning “better” or the idea of “different” meaning “better,” when we're looking for something different and we're translating it into better, which I would argue happens on very elite levels.

Like when you look at the United States Barista Competition, a lot of people use a lot of the same coffees. They evolve over time, they change over time. And they're often new or different coffees, but they're often the same [as one another], which I think is really interesting. But it is about us. It is not about what's actually happening on farms.

Ted: Exactly right. And the way you phrased that to me when I sort of realized that in doing this research that was really powerful, that anything that we call better, we have converted that from different, so the different-to-better translation is super important. And it does happen in an elite level.

It's not completely top-down though, right? It's not a cabal of people at the Specialty Coffee Association meetings or getting together in Portland and deciding it. People try something a little bit new and you're like, “Hey, try this. What do you think?” And some of it pops and some of it doesn't.

Ashley: I wanna come back to this idea of third-wave and neoliberalism, because I think for me, that made me question a lot of what I had been doing in coffee or the way that I had talked about coffee in the past.

In 2015, I was a coffee trainer and I would do these public cuppings and I would talk about the coffees that we sold at the roastery—I worked for a roaster and we'd have all our coffees out on this table, and a really common question that I would get from people attending the cupping, tasting all these coffees is, “Are any of these coffees organic? Are any of these coffees Fair Trade?”

The way that I would circumvent that question, and I genuinely believed that I was talking about a thing that was better—and in a way I was—is that I would say that, “No, we circumvent the certification processes to work directly with farmers so that we can pay them more.”

And that is factually true. That is what we did. We directly worked with farmers and generally paid more than whatever the fair trade floor was, because I think the Fair Trade floor, I think right now it's $1.40 per pound. But it fluctuates based on what the C-market is. It always guarantees a higher rate than the C-market.

But what we forget when we say something like that is that we're cherry-picking who these farmers are—and going back to that chart that you made, it's like, you have 11 farms on there. One is getting $4-something a pound, the rest are getting $1.

Ted: And generally they're not the smallest, most needy farms that saying “we work with small farmers” would imply.

Ashley: Right, exactly. And it calls to question, how do we make these choices? How did we get to work with these farmers? A lot of it is that—do we have access to this farmer? Did we meet them at an event because they speak English? There's all these different ways that roasters can get connected with farmers that don't have anything to do with the coffee itself, but often have to do with a privileged position, like you were saying.

These are often farmers who maybe aren't as needing—and I don't wanna judge needing too far or get too deep into that. But the idea that we're making these decisions about like, one farm is gonna get this money and then the rest aren’t. But we do have these collective organizations like Fair Trade, like organic certification—maybe organic certification is not in that conversation, but Fair Trade or maybe other certification programs that try to do more for a collective, perhaps? I'm not sure if I'm summarizing that correctly.

Ted: No, I think that that's right.

Ashley: So yeah, how do we talk about that? How do we talk about what might be good for a group might not necessarily be the way that we're selling coffee, if that makes sense. As I was reading this book, it made me think like, “Were we better in the second wave?”

I don't know what the answer is to that—I would say that people are gonna listen to this and be like, “Absolutely not. There's no way—there's just no possible way we were better in the second wave.” But as I think about systems that we put in place for larger groups of farmers versus the exceptionalism that has persisted in the third wave, I have to think: Did we take a step backwards in actually building equity?

Ted: But Ashley, once again, you're being provocative…

Ashley: I am—I don't know. I don’t know!

Ted: Well, it's the right question, and I think you set it up right and not overdetermining what that answer would be. There is so much to be celebrated in the third wave, and those of us who are into coffee, we’ve benefited from this surge of different kinds of coffees and flavors and tastes and stuff. And even the intentions are really good. The direct relationship intentions, as you were saying. Specialty roasters and coffee shop owners—so many of them are trying to do the right thing, but how do you do that?

Okay, I need to talk to my importer and see if they can set me up so I can meet a farmer and I'm gonna go to origin, and they're gonna set you up with somebody who kind of speaks your language, if not literally English, at least understands what the market that you're selling to is.

And so again, it's nobody's bad intentions, but it does orient this all toward more rather than less privileged farmers that way. It also, and I wanted to come back to your point about the collective versus the individual, and this is why it's neoliberal. So neoliberalism is very good at rewarding individual excellence and winner-take-all markets.

Sports is probably the best example. A little bit of difference makes a huge difference in pay. And it's become that way in the third-wave market. Just a little bit of an edge in terms of a quality standard makes a huge difference in what farmers are getting paid.

Highlighting the individual: That's well and good, and most of the Mayan farmers I know would embrace a system like that. They would say, we work really hard, we produce really good coffee, and we would be rewarded for our efforts—we're all on board with that.

But in fact, it's really hard. You've got a smallholding farmer that's producing 15 bags or 22 bags of coffee a year. Just processing that on its own is really tough. And so they really prefer to work through cooperatives. But buyers who are looking for micro-provenance coffee, they don't wanna buy from a cooperative that 25 farms that are pouring cherries into the processing vats. They wanna buy from one farmer and tell that one farmer's story.

Ashley: I go back to that map that you put up and thinking about what you were saying: Of course, people wanna be rewarded for their hard work. Looking at that map, all of those farmers are working hard and I think that's what makes third-wave exceptionalism kind of scary, because I think it's easy to say that we reward quality—and quality is something that we haven't talked about too much in this, but quality is often codified into…

Ted: Numbers.

Ashley: …into how we pay for things, and it's easy for us to justify, “Oh, we paid $4 a pound for this because of the quality.” That's like, as you demonstrated in the work that you did, by taking those coffees and having them cupped, everyone's working hard and the quality is often there.

Ted: That’s right.

Ashley: So how do you make a choice?

Ted: It can be kind of paralyzing or disconcerting or disheartening as you were suggesting. I would also say there's another more optimistic narrative that okay, let's say the neoliberalism system is in place and we're having to work within that.

We can identify a market failure. There is great coffee being produced that's sold for much less than its market value. So then how do we make up for that? And there's not an easy answer because, I mean, somebody producing 20 bags of coffee—coffee is sold internationally in container loads of 40,000 pounds.

There are a lot of logistics to be worked out, but there's also an opportunity there.

Ashley: Yeah, and I think it's okay to be clear about what you value, too. Like you can't value everything. But I think the idea that value can be quantified and there is only one way to interpret value is what has really harmed us, and that's why, I would argue, a lot of coffee roasters look the same. A lot of the ways that coffee roasters purchase coffee look the same because we've placed so much value on these singular economic prices, scores.

We've quantified quality in this way that I don't think quality can really be quantified, especially when we actually look at our values, like what do we value? And again, we don't have to value everything. It's okay to be a roaster who values working only with women producers. It's okay to be a roastery that only values working with partners who are maybe very close to where you live. That's all relevant and that's all important—but that's not how coffee works.

Ted: No, and it kind of hides this translation of symbolic aspects and narratives. “This was grown in this remote farm where the rainfall is tremendous every year…” and all of these stories that do go into our value of [coffee], but the focus on numbers really hides the way in which all that happens.

Ashley: There's this chart on page 207—it's right towards the end of your book—that I thought was really interesting, and for me it really solidified why this conversation is really important. So you break down the value distribution of coffee into two market segments based on coffee's quote unquote “three waves.”

So you have how much coffee is sold, US per pound, in the first wave, how much in the second wave, how much in the third wave. And then you break down that number based on how much of that value is going back into consuming countries and how much of that value is going back to traditionally producing countries.

And as the chart goes up—coffee is sold for way more in the third wave. You can't argue that, but the share of value going back to producing countries, going back to traditionally producing countries, is significantly smaller in the third wave than it is in the first or second.

Ted: That's right. I'm so glad you pointed that out, because I think that's a really revealing chart. And so it's important to say that absolutely the number, the amount in the third wave that producing countries receive is still higher than second wave and in first wave, but as a percentage of the total price, it is much smaller.

And so on the one hand, and you can play this narrative two ways, right? “Oh, look, producing countries are receiving a lot more than they were 20 years ago,” or you can say, “Boy, producing countries are receiving a much smaller percentage of final price than they were 20 years ago.”

Ashley: How do you put those two together then? How do you try to parse those out? Because I think you're right—there are two ways to look at it. How do you even start to understand it?

Ted: Well, I think that it goes back to the dearth of cultural capital on the part of the smallholding producers. I think that they could capture more of that value and they don't even have to roast, but if they could own their story a little bit more. And this is what those successful, medium-to-large-size farms have done.

El Injerto in Guatemala, where I work, is a great example. They produce great coffees. They're not a small farm. We could argue if they're medium-size or whatever they are, but they know how to tell the story that sells well in the United States and they're able to take a much greater percentage than real smallholders.

Ashley: As roasters, how do we start to do some more of that work? The royal “we” is applicable in this since neither you nor I are a roaster. But I would argue, and I think I've said this a couple of times on this show, roasters could take more risk. There is more risk involved in coffee producing, and even in your book you mentioned part of what happens in neoliberalist structures is that risk gets pushed further and further down the chain to people that are most vulnerable. So how do we look at this problem and say, “Okay, how do we assume some of that risk and how do we bridge that gap?”

Ted: That’s a great question, and a pressing dilemma. I think on the one hand, sort of easy, actionable kinds of things: when a roaster wants to establish a direct relationship, really push the importer/exporter to introduce them to a wider range of producers.

Even just a little bit of a push and nudging that way I think could could move the needle somewhat. But what you're getting at is this larger structural problem and where risk is distributed in the coffee market. And I like your idea of roasters or the consumption side at large taking on some more of that risk.

I used an example of, I gave a talk to a non-coffee crowd, and I used the example Blue Bottle is selling an El Injerto Pacamara natural right now, for I think $55 for 100 grams. Again, this is in Huehuetenago, Guatemala, where we did that study you referenced earlier. There are all kinds of smallholders around there producing equally interesting coffees.

So capacitating producers some way to sort of having those kinds of relationships where roasters can talk to producers and share more of that knowledge and show producers what is even within their realm. I know I went a little off there.

Ashley: No, I totally see what you're saying though, because so much of the disconnect between what consumers are seeing and what producers are seeing—that's where it all lies, right? That's where the disconnect lies. And being able to have access to like, “Oh, that's what the market looks like. I can do that, no problem,” is part of the solution.

And like you said, it involves all this cultural capital of being able to go to an SCA event and see what people are consuming, talking to roasters in a language that both of you are comfortable with, having that cultural capital to kind of ascertain what's happening in the market is really key.

Maybe I'm being a little pessimistic—you can be the optimist, I'll be the pessimist here. I wish I saw more roasters attempting to bridge that gap and maybe hearing a conversation like this will alert them of that gap. Because again, one thing I liked about your book is that you open up with this idea that there are people truly trying their best and there's a lot of that in the third wave.

This idea that we are doing our best or we're trying and there's a lot of value in what we're trying to do. So how do we reframe that? How do we take that to be like, “Okay, how do we see outward more?”

Ted: And in all fairness, it is a heavy lift especially for smaller roasters, right? Struggling to get by, trying to create a market for yourself. Trying to present these coffees that you're excited about in a way that you can get other people excited about. That's definitely a full-time job just focused on the consumer end.

But I think you're also right. There is a potential there to not only present these coffees that one has found to a consumer, but to do that hard work of translating, of finding smaller producers and really translating that—that's the sweet spot.

Ashley: And we already have an example of that. That's how the third wave works. And you've rightly identified that in your book, that value is coming from being able to translate the symbolic value of coffee. So we have the tools.

Ted: That's exactly right. That's the reason I'm an optimist about these things. There are so many good intentions. I was just struck doing this work on the coffee book and interviewing lots of specialty and third-wave coffee professionals at just the virtue that was expressed, the dedication to craft, the wanting to make markets more just, these are all real sincere sentiments and I think what is needed is what you're suggesting, is a pathway.

I'm sorry, I don't have the silver bullet solution there. There isn't an easy pathway but there's a lot of possibility right there, right now in the market.

Ashley: I cannot recommend this book anymore. I learned so much reading this, I learned so much about big ideas, about small ideas, about the historical context of coffee. I think what I'm finding especially valuable too, I finished reading this on Saturday, and I still have like a hundred pages of footnotes to go through, which is really exciting cuz that means that there's more to read.

It's so well-researched. I saw so many articles that I was like, “I need to read more on this.” Like I said, the footnotes are incredibly rich as well, and I am so appreciative that they're such an exhaustive book that … I don't know, going back to this idea of optimism, it's like you can ask hard questions and still be an optimist and I think that you really convey that in this book because you do ask a lot of hard questions and you give a lot of hard truths, but at the same time, you don't close the door on a better future.

Ted: Ashley, that's the best endorsement that I could possibly have. And it is such a treat to be here, a longtime listener, first time caller here, and so it's a real treat to be here with you.

Ashley: I usually end these conversations by asking the guest is there something that you want people to know about what you're doing or the work that you're involved in that maybe we didn't cover that you want people to know about?

Ted: That's a hard question. I essentially tried to put everything in the book!

What I will say as an educator—and we do have this, this Coffee Research Institute. I'm teaching a class right now on coffee, and there is such an interest on the part of my students in learning about coffee, and it is such a great way to explore environmental change and plant biology and the way in which colonialism, the legacy of colonialism, has really structured so many of these markets today.

I guess I don't have a specific thing that I would like to to share, but just the potential for further researching coffee is so enormous.

Ashley: Ted, thank you so much for taking the time to chat with me. This has been awesome.

Ted: My pleasure.

Differentiating Between 'Value' and 'Values' With Ted Fischer